Through Period Documents

Writing historical fiction is a challenging but rewarding endeavor and requires writers to handle a myriad of different historical elements on top of crafting an engaging story. One thing to consider is making sure the voice of your characters, whether you write in 1st or 3rd person POV, fits the time of the story and doesn’t jar your readers with words and speech patterns that don’t fit the era.

While you’re under no obligation to write exactly as people would have done in the 1860s, knowing how people spoke at that time, the popular slang, and the way they communicated can help you craft a deeper, more believable setting and help bring your characters to life, making them much more memorable for your readers and helping your work stand out, especially for the people most interested in the time period you’re writing in.

The best way to get a feel for how people spoke at a given time is through reading their own words in letters and diaries. While you can also turn to novels written at the time, in that case the words you’re getting are already going through the filter of another writer, who was obeying the writing and story conventions of their time, meaning that you will encounter more distortion than if you focused on unedited letters and diaries.

The Research Arsenal has thousands of letters and many diaries all written in the mid-19th century available to read and they can give you amazing insight into varied speaking and writing styles of the time. By browsing through this collection, you’ll quickly be able to hone in on a variety of insights on how people spoke and be able to incorporate those into your work.

Slang and Common Turns of Phrase

Every generation has its own slang and idioms that characterize it. For writers working in the era of the American Civil War, some of these terms, like “Rebs,” “Johnnies,” and “Secesh” (short for secessionists), to describe Confederate soldiers, may already be familiar. But there is a wealth of other slang and turns of phrase that are waiting to be discovered.

“Played Out”

It is hard to read more than five or ten letters before coming across one where the writer complains—or hopes—something is “played out.” In a letter written in 1863 by Corporal Albert Henry Bancroft of the 85th New York Infantry, he tells his brother, “The weather has been cool and pleasant for near [a] week although it has been wet most of the time and we can sleep nights and not hear the mosquitoes for they are a wicked set and swear dreadfully if they cannot taste of you. They have been plenty since the first of May. But I hope they are about played out.”

Another writer, Private Lloyd Willis Manning of the 3rd Massachusetts Heavy Artillery, wrote to his wife asking her to send him a new cap because his was about “played out.” Excerpt below:

“[…] will you please send the hat and socks in preference to a letter? My socks I have to take them off and wash them and wait until they get dry before I can have any to wear. My old cap is all played out and if I have to wait much longer, I shan’t have any.”

This excerpt also highlights the no longer common use of “shan’t” rather than the more modern sounding “won’t.”

“On Account of”

While not exactly slang, there are many sentence constructions that have changed over time and using versions more common to the mid-19th century is an easy way to create a voice that feels of that time, without using any slang that might leave your readers confused.

In mid-19th century texts, there is a tendency for writers to have a preference for words of French etymology rather than old English. For example, it’s more common for writers to talk about “commencing” something rather than “starting” it, which is in direct contrast to most writers’ preferences today. The Google Books Ngram data below shows how the use of “started” didn’t overtake “commenced” until sometime in the 1890s.

“I received your letter some time ago and have neglected writing partly on account of having so much of my time occupied in studying and partly on account of having no particular fondness for letter writing. I hope you will excuse me this time and I will promise not to be so dilatory again in writing.”

In his letter, Wilcox does not use the word “because” at all, instead employing either the phrase “on account of” or using “as” instead of “because” in the sentence “I had to forego studying this evening as I wished to write to you.”

The great advantage of working phrases like this into your writing is that you can be sure your readers will still perfectly understand your sentences while still gaining a feeling that the character speaking is of an earlier time. You’ll also be drawing on authentic speech patterns and creating greater and more immersive realism in your text.

Civil War Era Letter Writing

Letter writing has evolved over the centuries, and there are numerous small details in Civil War era letters that you can use to bring greater authenticity to your fiction, especially if one of your characters finds themselves putting pen to paper. These details include how people addressed each other in letters, their general narrative style, as well as how they used the paper itself and their expectations of when and how letters would reach their loved ones.

One of the most glaring differences between modern and mid-19th century letters is how differently letters are addressed to each other. It is not uncommon to find letters addressed to “Sister Mary” or “Friend John” whereas in modern times we would often leave off the relationship we shared with the addressee. Frequently, letters were meant to be shared with the whole family, or even the whole community, and would be addressed simply as “Dear Folks at Home.”

If writers wished for the correspondence to be more secret, they would—somewhat unbelievably—write “private” at the top of the page to signal it wasn’t meant for everyone to see. There were other options such as using ciphers but in most cases a letter requiring that kind of secrecy did not survive long after being read and it was a common practice at the time to burn letters after reading them if they were of a private or intimate nature.

Another facet of letters that modern writers would find unusual is how they are often written in a style where the writer directly addresses the reader and narrates precisely when they start and stop writing a letter. This is common throughout letters but tends to occur more frequently when the writer comes from a background with less formal education. “Well” is also very common to see as a sentence starter with some writers using it nearly every sentence as seen in this letter by Edwin Whipple:

“Well mother, I have been to work all day down at the Landing handling lumber and have just got back to the tent and found your letter laying on my bed. Well, you want to know how I found my box.”

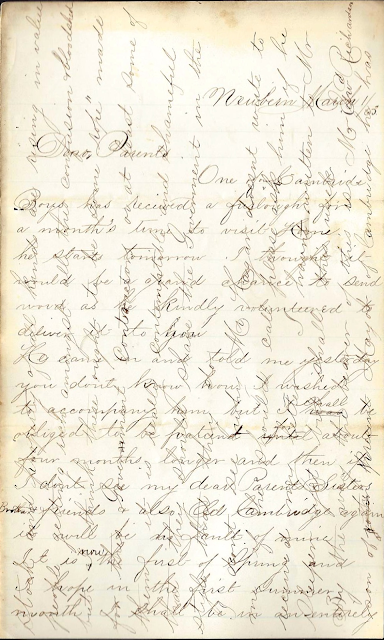

One of the most surprising aspects of letter writing during this era is how often extreme measures would be taken to conserve paper. While this is not a detail that relates directly to a character’s voice, it can give you insight into how people of the time conserved resources and learned to make do with what they had.

Most of us are no strangers to trying to squeeze in a few extra lines at the end of a page, but some people in the mid-19th century had a much more systematic approach to getting the most out of each sheet of paper. This involved turning the sheet sideways after they had filled it up and then writing over all of their original writing perpendicularly. It makes for slow reading but is usually still legible.

Conclusion

The examples above only skim the surface of the many ways you can improve character authenticity through studying period letters. The more letters you read, the better feel you’ll have for how people of the time thought and spoke. Through incorporating common slang like “played out” and using words like “commenced” instead of “started” you can incorporate the feel of the times without sacrificing readability of your stories for modern audiences.

By reading through period letters, you’ll be able to make further observations of your own and use those elements to strengthen your characters’ voices. Deciding how much of your discoveries you want to include in your characters’ voices is a personal choice, but the knowledge you gain from studying these letters will give you invaluable insight in crafting a more authentic experience for your readers.

Click HERE to check out the database.

This database really is a game changer and we have secured a special 15% discount on The Research Arsenal's annual membership.

Just type in YARDE at the checkout.

Excellent article! But I did have to laugh a bit about one of the first idioms mentoned as notable during the Civil War—“played out.” This phrase was commonly used by my own family. Granted, I did grow up in the 50s and 60s—the twentieth century, that is, not the nineteenth!

ReplyDelete