Publication Date: 24th January 2022

Publisher: Sharpe Books

Page Length: 261 Pages

Genre: Historical Mystery

Congratulations on your recently published novel, Rome's End (Lucius Sestius Mysteries Book 1). What drew you to write about the Sestius family and in particular, Lucius Sestius Quirinalis?

Thank you! I first came across Lucius when he was about twelve years old and getting ready to sob on cue during a major trial in the Roman Forum. Cicero the great politician and orator was defending Lucius’ father, Publius Sestius, and this defence speech still exists. Of course, the speech is mostly about Cicero himself, but young Lucius appears a couple of times, and I really felt for him: just when he is entering the age when being cool matters, he has to be ready to respond when the lawyer declaims: “I see the defendant’s son, with tears in his eyes…”

The Sestius family get several mentions, so I was able to reconstruct an older sister and a stepmother for Lucius, and I began to search outside of this speech. Lo and behold, I discovered that Lucius was on the side of Brutus and Cassius after the assassination of Caesar – and he even helped run a mint for Brutus, producing coins whose imagery reinforced Brutus’ message of being a Liberator rather than an assassin. I cannot describe to you the excitement when my husband actually tracked down one of those coins! It’s one of my most precious possessions, and I can still read his name SESTI running around the edge.

|

| This coin, belonging to the author, shows the head of the goddess Liberty on one side and the implements of sacrifice on the other. |

Twenty years later, Lucius suddenly pops up in the lists of Consuls. In other words, the rebel from the forties BCE gains Rome’s top office in the twenties BCE. What brought about such a change? And so I started to write to explore that transition.

When researching this era, did you come upon any unexpected surprises?

I was investigating what the Romans ate and was not expecting to discover that a group of archaeologists are analysing the contents of a latrine pit in Herculaneum, a town on the bay of Naples destroyed in the eruption of Vesuvius. The research is fascinating, and it turns out that the inhabitants of a rather ordinary block in a small town ate fish, poultry, vegetables, fruit, nuts and pulses, a varied and healthy diet that modern doctors would find hard to fault. I was once more impressed by the dedication of scholars who spend their days analysing – let’s face it – poop, to add that extra bit to our knowledge of our world. Over seven hundred bags of material were collected! Interestingly, several lamps were also recovered – imagine visiting the latrine in the night, you are sleepy, you stumble, and before you know it your lamp has gone down into the depths…

|

| Terracotta oil lamps like this were common all over the Mediterranean. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons in association with the Metropolitan Museum. |

Why do you think this period in history is still really popular with readers?

It has everything – extraordinary characters like Julius Caesar, violence, literature, war, architecture, political conflict.

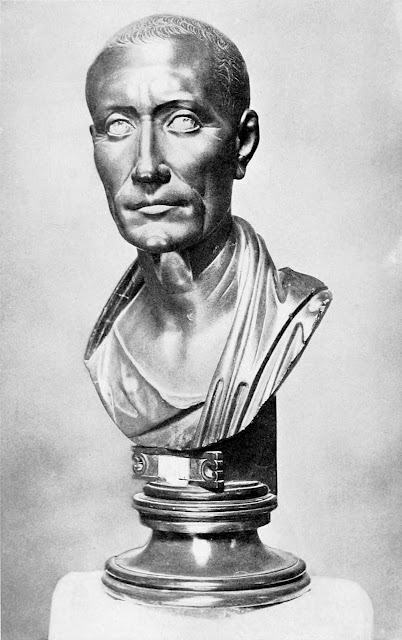

|

| Julius Caesar bust portrait here. Caption: Julius Caesar. Unknown sculptor and photographer, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. |

And, crucially, a lot of the evidence survives, not just written, but physical, so we can walk around Pompeii or Ostia and imagine how people lived. This is very attractive: there are times when I can read a poem by Catullus or a letter by Cicero and feel the gap of the years between us shrinking. Then I remember that the Romans hunted animals in the arena for sport, and executed people - often in the arena too, as entertainment - using crucifixion.

|

| This large cat was killed in the hunt, as is shown by the mark above it. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. |

The reader’s desire to understand is constantly thwarted by the Romans’ acceptance of issues which we find abhorrent, but we keep reading because this is still part of the human story. It is worth repeating: if we study history, we learn about ourselves.

What do you think is the most challenging aspect of writing Historical Fiction during this era?

How to explain material without either patronising the reader or flooding them with information! I have to be reminded – over and over again – that not everyone wants to know the minutiae of Caesar’s Civil Wars or what Cicero said in such-and-such a speech. I think people are genuinely interested in the ancient world and how it worked, the challenge is to meet that interest without a rather dry history lecture. Having said that, I do love learning from fiction myself. At University, I wrote one essay in my finals based on Robert Graves’ “I, Claudius”. I pretended that my source was the second-century biographer Suetonius.

Does one of the main characters hold a special place in your heart? If so, why?

Oh, Cornelius Rufus has my heart and always will. My hero, Lucius, is a sweetie, and finishing the third book in his trilogy is breaking my heart, but he is also what my mother would call “gormless” (a great word to describe someone who hasn’t a clue). Cornelius Rufus on the other hand is sharp and knows everything going on. He is the intelligence gatherer employed by the Sestius family to collect gossip – if they need to know the dirt on a political opponent or someone they are prosecuting, they call on Cornelius Rufus. Lucius is a little snobby about him because he comes from the Subura, Rome’s high-rise, low-rent area where you don’t go after dark. But Cornelius Rufus is resourceful and genuinely fond of the Sestius family, and Lucius comes to rely on him. If I had to describe them in dating terms, Lucius would forget to turn up, but Cornelius Rufus would be on time and bring flowers.

Prologue

The crowd in the Forum falls silent as the Consul comes down the hill, towards the Speaker’s Platform. He looks at the ground as he walks, a thoughtful expression wrinkling his brow, as if he imagines posing for a statue of himself at this critical moment. The young slave, who has been posted near the Senate House steps, straightens up and shifts nearer to the platform, along with everyone else, and tiny noises of movement swell to a whisper that runs through the crowd then dies away as the Consul faces the people of Rome and opens his mouth to speak. Torches – for it is nearly dark now –hiss and spit and light individual faces which seem to spring out of the crowd, eyes narrow with concentration or wide and frightened. The Consul seems about to speak but checks himself and takes a deep breath.

The slave is now at the front of the crowd and hopes that everyone will keep calm. He wishes the Consul would get on with it, instead of dramatising the occasion still further. He watches the lines across the Consul’s brow as they deepen slightly, and waits, wondering briefly how the Great Man could possibly deliver yet another memorable speech at the end of this year of speeches. He knows what news the Consul has to deliver – everyone knows it. It is a question of how he says it, and the slave concentrates, knowing that he will have to repeat as much as he can remember when he gets home.

“Vixerunt,” says the Consul very clearly, and pauses. The crowd sigh, and then hush again, and the slave shivers. But the Consul is turning, going down the steps once more. The crowd begin to talk excitedly and the slave feels his mouth open in surprise. “They have lived!” A single word – didn’t the occasion demand more? Surely Marcus Tullius Cicero, greatest orator in Rome, could have dredged up a few florid phrases to commemorate the most important day in his career? No – so perish all enemies of Rome and not even their epitaphs are allowed to commemorate their deeds.

It takes the slave a long time to get out of the Forum, because of the numbers of people moving slowly, as if no one wants to leave. Once on the road up the Caelian Hill, however, he moves quickly and even runs along the little side street leading to the Sestius house. Young Lucius is waiting in the atrium, of course, and so, to his surprise, is the master’s new wife, Cornelia. They both run up to him – there isn’t much unnecessary ceremony in the Sestius household.

“Decius!” cries Cornelia. “Is it...?”

“Are they dead, Decius?” says Lucius, looking very serious.

“Come into the study,” says Cornelia. “There’s some water there for you.”

The woman and child lead him in and fuss around him, making sure that he is comfortable. They sit patiently while he drinks, the only sign of their eagerness the fierce way in which the five-year-old Lucius swings his legs as he sits on a couch that is too high for him.

“They’ve just been executed,” reports Decius. “Cicero has just announced it in the Forum.”

“What did he say?” demands Lucius.

“He just said, “Vixerunt,” says Decius.

“They have lived? That’s a funny thing to say when you’ve just executed someone,” says the boy scornfully.

“It’s the traditional way of announcing an execution,” says Cornelia. “It’s bad luck to mention death itself.”

“Only for Lentulus and the others,” says the boy cheerfully. “And they deserve it for plotting against us all. That’s what Father would say.”

“I’m not sure that your father would say that – not quite. And anyway, you mustn’t think about it anymore,” says Cornelia. “They were wicked men, but now they’ve gone, so we don’t have to worry.”

“But Catilina’s not gone, is he? And Father will have to fight him before he goes,” says the boy. “My tutor says there will be a big battle. Do you think there’ll be a battle, Decius?”

“Yes, I do, Master Lucius,” says Decius. “But I don’t think your father will enjoy it. It isn’t a glorious thing, Romans fighting Romans.”

“I don’t think Father would enjoy any battle,” says Lucius sadly. “He’s not really a fighting sort of person, is he?”

“Your father will do his duty, and that’s what matters,” says Cornelia. “Now you have heard the news, have something to eat – only a snack, mind – and go to bed.”

Obediently, Lucius jumps down from the couch and takes Decius’ hand.

“Have you ever seen Catilina, Decius? Is it true that he really looks monstrous?”

“He is certainly not a monster,” says Cornelia, firmly. “He’s an ordinary man, just like your father, except that Catilina wants to take over the country, which is wrong. Now go to the kitchen and tell Melissa I said you could have a snack. And I don’t want to hear that you’ve been pestering Decius with questions.”

The boy and the slave leave, and their voices and the light patter of their sandals die away as they go off to the kitchens. Cornelia puts her hand on her belly, and sighs. What a time to be having a baby! She thinks of her husband, who has spent the last three months patrolling down in Capua and returned to Rome a week ago only to set off immediately for Etruria where Catilina and his troops are mustering. She crosses to the small shrine in the corner and puts a pinch of incense into the burner, whispering a prayer that the gods will protect Publius Sestius and bring him safely home to his family.

.png)

Rome's End sound amazing! Thank you for sharing, I am heading over to Amazon!

ReplyDeleteA really interesting post, thank you for sharing. Your book sounds fabulous.

ReplyDeleteI loved the book, and really enjoyed hearing more about how you came to write it, Fiona.

ReplyDelete