Who Do You Think You Are?

I got my first good look at the Declaration of Independence when I was nine years old. The United States Bicentennial celebration was in full swing, and Spirit of ’76 themes were popular, well, everywhere. Even the local McDonald’s had updated its décor with an American Revolutionary theme. As I sat in the red plastic booth with my Happy Meal, staring up at the life-sized reproduction on the wall over our table, I saw my name. Well, my last name, anyway.

Someone named Tho. Stone had signed the Declaration of Independence three lines below John Hancock. I wondered if my family was related to him but dismissed the idea as impossible.

Many years later, I learned Thomas Stone, signer of the Declaration of Independence, is my second cousin seven times removed. Does that make me feel better about myself?

Probably, say psychologists.

A study conducted at Emory University and published in 2010 involved asking children a range of questions such as whether they knew where their parents met, where they grew up, and where they went to school. The study found the more children knew about their family history, the higher their self-esteem and the better able they were to deal with the effects of stress.

Encouraging teenagers to dig into their family history helps strengthen family ties, whether the history is that of a parent or grandparent, or someone much more distant. Knowing more about the events in our family members’ lives helps us understand each other better and can even bridge those gaps of disconnect between parents and teens.

Family stories informed me that my dad’s ability to build or fix almost anything is something passed down from his ancestors, who built and ran a saw and flour mill. That my sister’s passion for helping people, which led her to medical school, is not unlike that of our great-grandmother, who was a dedicated nurse during the Spanish Flu epidemic.

While compiling a family genealogy as a gift for my parents’ fiftieth wedding anniversary, I learned of the adventures of my patriot ancestor Anna Asbury Stone. My heart swelled with pride to learn of her brave deeds. So when, a few years later, we were listening to a podcast and the host said, “We rarely see history from a woman’s point of view,” I realized I could do something about that.

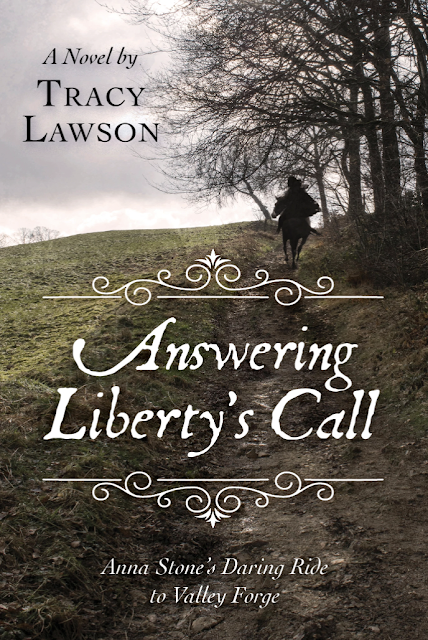

My debut historical novel, Answering Liberty’s Call: Anna Stone’s Daring Ride to Valley Forge, uses the family tale as a framework, and is full of insights into what life was like for women during war time. My extensive genealogical and historical research uncovered amazing details about Anna and her husband, Benjamin, that shed light on their motivations and heightened my admiration for my six-times great-grandparents. They were an American Revolution power-couple. Telling Anna’s story connects me to my past, and to every American.

Fauquier County, Virginia

January 5, 1778

My cousins Mollie and Nancy gathered around my aunt Jean at the pianoforte, and as the opening chords of the ballad “Turtle Dove” tore at my heart, I picked up baby William and dodged my mother’s restraining hand.

“Anna, stay and listen to the music.”

“He needs his napkin changed.”

“Do you forget we have servants for that?”

“Don’t trouble Phillis or Lynn, Mother. I’ll do it.” My cousins’ voices drifted after me as I hurried from the room.

Fare you well, my dear, I must be gone, and leave you for a while; if I roam far away, I’ll come back again, though I roam ten thousand miles, my love…

Upstairs, I shut my chamber door to muffle the rest of the song, hugged William close, and fought back tears. No letters, no word from Benjamin in two months. Most of the time I could bear his absence, but tonight I missed him so keenly I was terrible company. Time spent changing little William’s napkin would grant me a short respite from my family’s Twelfth Night celebration.

Our son’s dark hair and bright brown eyes resembled his father’s, and when he smiled, my warring feelings of joy and sadness threatened to overwhelm me. How I would have preferred to be at home, with just Benjamin and our children. Instead, he was somewhere in Pennsylvania with the army, and the children and I were in exile at my uncle’s house. Our young ones had no memory of fat turkeys, mistletoe, and simple, cozy holidays spent at our dear little home near the apple orchard. The house stood empty and forlorn for a second winter. My own memories were fading.

The baby chortled as I kissed his feet in their knitted booties. “Your father will be so excited to meet you when he comes home, my sweet boy.” When that would be, I could not say. Though it was like picking a wound that wouldn’t heal, my eyes strayed to the ribbon-bound packet of letters on the escritoire. Better to stay in my chamber, where it was quiet, and re-read every one of Benjamin’s letters.

I had long been under the spell of my husband’s words. Most of our courtship was conducted by correspondence, and even now, after ten years of marriage, his writing and oratory skills kept their hold on me. In the pulpit, he had the power to lift a congregation. In an ordinary, he could raise a mug of ale and inflame the passions that drove men to seek political change. I often faded into the background of his public life, just as he let me tend to mine without interference. But at home, we treasured our intellectual discourse. It was one of the many facets of our marriage that bound us, one to the other. At home, we were equals.

I suppose that was why his decision not to consult me before arranging for me to live here, at Uncle’s, still hurt.

***

I hadn’t protested when Benjamin enlisted in the Culpeper Minute Men in the fall of 1775, for it was every able-bodied man’s duty to serve in the militia. He’d been delighted—far more than I, to be honest—when the Virginia Assembly called the Minute Men to defend the arsenal at Williamsburg just before Christmastide. When he’d returned three months later, he was restless, and a chasm formed between us that had not existed before. Even though Governor Dunmore’s expulsion from the colony had restored peace to Virginia, Benjamin would not be content until the unrest in all the colonies was resolved.

The following spring, I had quailed with fear when the main army attached his militia unit to one of the Virginia regiments. But months passed, and despite the escalating conflict, Benjamin was not called to do anything more dangerous than take a turn guarding disaffected Loyalists from Virginia’s tidewater coast who had been brought inland to Fauquier County.

Though he spent long days in the fields or the orchards, he often rode off after supper to spend a few hours at Edwards’ Ordinary in nearby Fauquier Court House. There, he and his fellows followed the news of the continuing rebellion in the north and rejoiced in the daring exploits of the Sons of Liberty.

Unsure how to make him understand my worry, I settled for pointing out it did not look well when a preacher spent more time in the ordinary than in church.

One October evening, Benjamin was unusually quiet as he cleaned his rifle. Even after the children were in bed, he continued to polish the barrel in silence. This was our time for conversation, and I waited for him to speak his mind. When he rose and hung the rifle on its pegs over the door, I could hold my tongue no longer. “What troubles you?”

“I’m not troubled—just trying to decide how to tell you.”

As it happened, I had news for him, too. At the children’s bedroom door, my keen mother’s ear discerned Rhoda and Elijah breathing in unison. I took my shawl off its peg. “Come for a walk with me.”

Outside, our shadows melted into the darkness between the rows of gnarled apple trees that marched across our orchard’s hills. When the climb grew steep, he took my hand, steadying me until we stood together on high ground. Here the Blue Ridge Mountains rolled away to the east, the north, and the south. To the west, the last rays of the setting sun turned the horizon orange and pink. Silhouetted against the fading light, his profile put me in mind of a Roman emperor I’d seen in a book, and it tinged my surge of affection with foreboding. I’d married a farmer. A preacher. I had not expected him to become a warrior.

Pick up your copy at your favourite online bookstore - HERE!

Tracy Lawson’s passion for storytelling led her first into the world of dance and educational theater. In a career that has spanned nearly three decades, she has been a dance teacher, a studio owner, and to date has choreographed thirty-two musicals for middle- and high school students.

When faced with a mid-life career change spurred by a cross-country move for her husband’s job, Tracy adopted the motto, ‘have laptop, will travel.’ Within a few years, she had achieved a lifelong goal and published her first book, based on the 1838 travel journal of her great-great-great grandfather.

A series of post-apocalyptic novels aimed at young adults and a companion volume to her first nonfiction book followed. Currently Tracy has tapped into another family story for her debut historical fiction. While her body of work may seem varied, the common thread that connects all her books is her characters’ pursuit of individual liberty.

Tracy and her husband, economist Robert Lawson, both Cincinnati natives and graduates of Ohio University, have one grown daughter and two spoiled cats.

Social Media Links:

Website • Twitter • Facebook • Instagram

No comments:

Post a Comment

See you on your next coffee break!

Take Care,

Mary Anne xxx