Margaret hesitated and passed over her sketchbook. I shouldn’t be doing this, but the more I think about it, the more upsetting it is. Is this your friend? It’s the best I could do for a likeness. I didn’t see the man in the flesh – I mean the whole flesh. But someone took a photograph, and I drew his face from memory shortly after seeing it. Sketching bodies is part of my training of course, but also a hobby. It helps me work things out sometimes. It’s not perfect. The camera wasn’t focussed—’

‘On the face.’

She pulled an apologetic grimace. ‘Not in that particular photograph. There is one of his face, but not at a stage in proceedings when… I’m sorry. That sounds very callous.’

‘I understand,’ said Fox. ‘Some jobs are like that. You remain detached until someone reminds you what it’s about. It doesn’t stop the job from being necessary.’ He picked up the sketchbook and held it to the light. ‘Mmm. It doesn’t look very like him, rather too thin. But he hasn’t been seen for some time. It could be him.’

Margaret swallowed, and Dr Jordan’s words echoed in her brain. Signs of recent malnutrition. Instead of repeating them, she put her knife and fork down, and moved the plate with its half-eaten food to one side.

‘I can’t tell you more,’ she said. ‘I’ve probably said more than I should have already. But the poor man may have gone to his grave under a name that wasn’t his, and that always seems so cruel somehow. The workhouse said he was a tramp, but it’s possible he wasn’t. No one local knew who he was. There was nothing to confirm his identity. If it helps, I believe he died very quickly.’

‘Painlessly?’

Margaret stared into her cup and then looked up again. ‘No.’

‘I didn’t realise you were sentimental, Dr Demeray,’ said Fox angling the sketch. The light behind him made his hair bright, as if he had a halo. Margaret realised he was a strawberry-blond, the apparent darkness an illusion caused by whatever he oiled his hair with. Little reddish curls had escaped. His greenish eyes meet hers, and he tipped his head on one side as if to prompt a response.

‘I’m not,’ she replied, taking her book from him, their fingers touching for a moment. ‘But I do care. I am fully aware that the bodies I work on were once people and deserve respect.’

‘It’s why you do it, isn’t it?’

‘How do you mean?’

‘You want a better world for the poor. You want to prove living conditions are killing them.’

It won’t be hard to find out what your political leanings are, or your views on suffrage. Margaret’s sense of discomfort increased. ‘I’m sorry I couldn’t help you,’ she said. ‘And this has been very nice, but I must go. How much is my share?’

‘I wouldn’t dream of letting a lady pay.’

‘And I wouldn’t dream of being paid for by a stranger.’ Margaret stood up rather more abruptly than her ribs would have liked, and tried not to wince. Fox rose too. ‘I do hope you find your friend and that all is well with him. Perhaps another hospital—’

‘He wasn’t my friend,’ said Fox. ‘But I am interested in his fate. Eli Can, for want of another name, may have been him. What did he die from?’

‘Phthisis. That is, tuberculosis.’

‘I know what phthisis is. Was that all? I don’t associate that with a quick death.’

‘His lungs were extensively damaged by a number of things.’ Margaret put her sketchbook away and withdrew her purse.

‘Did they smell of anything unexpected?’

Margaret paused with a frown. She could recall nothing in particular above the general smells of the laboratory. Disinfectant, formaldehyde, and decay, together with whatever scents wafted in from the hot city outside the window: people, horses, fumes.

She shook her head and held out her hand. ‘Goodbye, er, Fox. As I say, I hope you find what you seek.’

‘It’s quite simple, Dr Demeray,’ said Fox. ‘I want to know what killed him. And who killed him.’

‘Who? Well, though you seem to know my views already, I believe what killed him was poverty, poor housing, bad working conditions, and damp … so who would be the slum landlords and the uncaring men in government who resist change.’

‘I don’t think you’re right in this instance.’ Fox dropped some coins on the table and taking Margaret’s arm, steered her through the tables and onto the pavement before she could argue. ‘In this instance, it’s much more specific.’

‘That’s ridiculous. Thousands of people die like Eli Can. One person isn’t responsible for all those deaths.’

‘I didn’t say one person was responsible. Eli is one of a very small number of people who have been killed in a similar way.’

‘Why?’

‘Why is easy. It’s the how and who that’s tricky. Goodbye, Dr Demeray.’

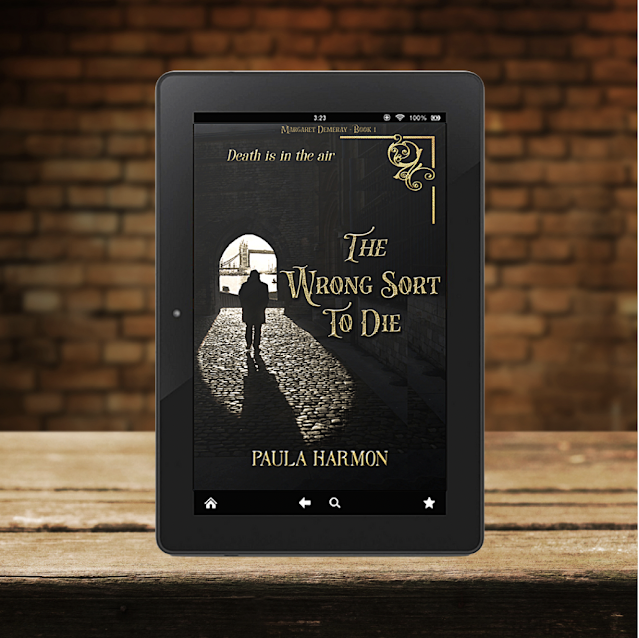

This novel is free to read with #KindleUnlimited subscription.

Paula Harmon was born in North London to parents of English, Scottish and Irish descent. Perhaps feeling the need to add a Welsh connection, her father relocated the family every two years from country town to country town moving slowly westwards until they settled in South Wales when Paula was eight. She later graduated from Chichester University before making her home in Gloucestershire and then Dorset where she has lived since 2005.

She is a civil servant, married with two adult children. Paula has several writing project underway and wonders where the housework fairies are, because the house is a mess and she can’t think why.

Social Media Links:

Website • Facebook • Twitter • Instagram • Goodreads

No comments:

Post a Comment

See you on your next coffee break!

Take Care,

Mary Anne xxx